Sam Hunter is a fiber artist and quilt pattern designer. Born in England, Sam split her formative years between Europe and the United States before settling in the USA permanently in 1981. Sam started sewing when she was only seven years old and then began quilting in her late twenties. Shortly thereafter, she started teaching quilting. Sam holds an MFA in Fiber Arts, and blends this classic training with a sense of play in all that she does. Sam has exhibited her artwork throughout the United States, and has received numerous grants and awards, including a Virginia Museum of Fine Arts Fellowship. As a pattern designer, Sam is a champion for helping beginners develop their skills, while making patterns that are interesting enough to entice more advanced sewists. Sam has developed a Pattern Mission Statement that informs all of the work she creates. In addition, Sam is a champion for artists getting paid a fair value for their work. She created the We Are $ew Worth It campaign to empower artists and designers by providing resources on topics such as: keeping track of time when working, pricing, and other issues that arise when trying to place value on the work that we do. Sam is the author of numerous patterns and the book, Quilt Talk: Paper-Pieced Alphabet with Numbers & Symbols – 12 Chatty Projects. Her beautiful collaboration with artist Lisa Congdon is currently touring with the Modern Quilt Guild’s Modern Showcase. Welcome, Sam!

Photo credit: Nancy Stovall.

How would you describe your quilting aesthetic?

Sam: “Not traditional” is probably the best thing I can say about it. Although I made my share of calico-based quilts when I started, it didn’t take me long to move away from them into a more contemporary vibe. I’ve dabbled in art quilts, too. The quilts that interest me right now as a maker are the modern quilts; but as a pattern designer, I straddle the contemporary and modern markets.

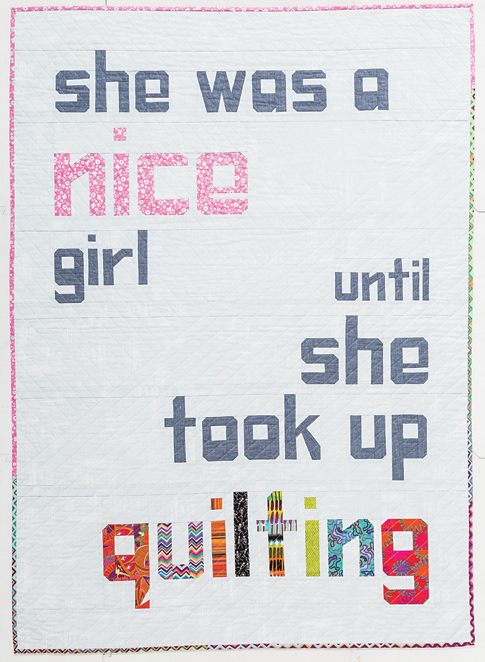

Nice Girl (from Quilt Talk) Photo credit: C&T Publishing.

How would you describe the creative environment in your home as a child?

Sam: I don’t remember there being much in the way of creativity going on in the house. My mom and grandmas sewed. But back then, all women did; I didn’t note it as a special skill. I had ample access to books (thank you, parents!) and grew up on the golden age of cartoons on Saturday morning television. At 6 years old, I would re-draw the comic strips from the Sunday paper, and I would imagine that I would become a cartooninst and draw things like Wile E Coyote, Road Runner, or Sylvester and Tweety cartoons. The first time I used my mother’s sewing machine I was 7, and I attempted to make a dress for a Barbie. Even as I cut out the first one, I was thinking, waitaminute, I need to add a bit on the sides for the seams or it won’t fit. That “figure out the puzzle” aspect has been a driving force for me in art. As a teenager, I was fascinated by typography. If I had known I could have been a font designer, I probably would have gone in that direction.

When I wanted to go to college for art, I was forbidden to by my parents. They threw up a lot of hurdles, and I just caved in the face of so much battle about it. I ended up going into technology (an electronic engineering degree). When I turned 30, I circled back around to beginning to the art degree I had always wanted . I took it all the way and earned an MFA in Fiber Art at 48.

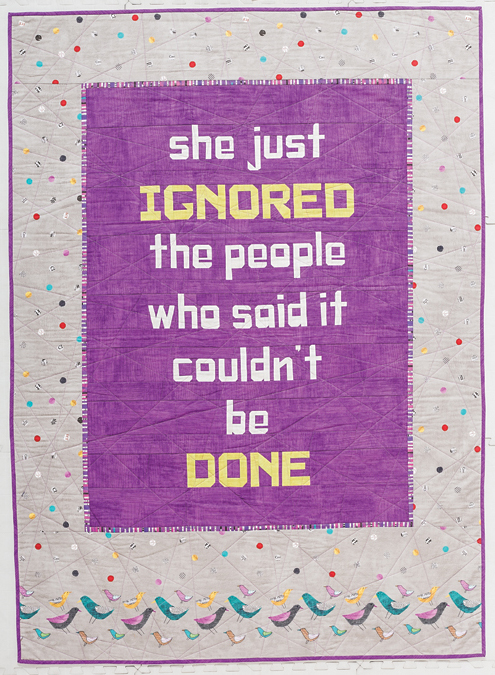

She Just Ignored (From Quilt Talk). Photo credit: C&T Publishing.

Which artists and makers do you most admire or have an influence on your work?

Sam: Outside the quilting realm, I would say that Barbara Kruger, Jenny Holtzer, and Faith Ringgold are high on my list. All of them work with words and language surrounding life, society, and the political sphere (either in general, or politics specific to women). Kruger and Holzer make amazing commentary pieces. Ringgold has made some work that asks very deep questions about what it means to be a woman in ALL her roles. I feel that it illuminates the complexity of women being held accountable to be all things at all times. The first time I studied her work, I sat, just bawling. I was 42, single, trying to work a corporate job while going to school part-time, and juggling a teenager too. Ringgold made a “story quilt” called “Wedding on the Seine” about a woman who got married, but ran out of the church after she said her vows, panicking that it meant that the depth of her as an artist was now lost to being a wife. At the time, my parents were pressuring me to quit school and “go find a man instead”. I identified so much with this character, just wanting more than the lot assigned to women of my generation.

In the quilt world, I admire a lot of our trailblazers who got out on the teaching circuit to spread the knowledge during the resurgence of the craft in the 80’s. Jinny Beyer (some amazing lessons in color theory), Libby Lehman (who taught me how to break down my machine to clean it), Jan Myers-Newbury (inspired me to learn to hand dye fabrics), Nancy Crow (major pioneer of the art quilt movement with Quilt National and the Dairy Barn). I also appreciate the women who made it welcoming for beginners to give it a go, like Nancy Zieman and Alex Anderson.

In contemporary times, what interests me is skill and mastery in specific areas. Jacquie Gering comes to mind for how she handles negative space. My pattern designing colleagues Kristy Lea (@quietplay) and Juliet van der Heijden (@tartankiwi) create foundation paper-pieced patterns that are not only cool to look at, but are elegantly designed and kind to construct. Jenny Haynes (@pappersaxsten) puts some color combos together that I find really interesting. I’m not huge on designing curves, so Jenny, and Jen Carlton-Bailly (@bettycrockerass) do work that fascinates me.

I could also name a dozen friends (and a few dozen more members of my guild) who have no aspirations for any type of quilt fame but, who are wildly talented, and I love hanging out with them because they make things that would never occur to me to try.

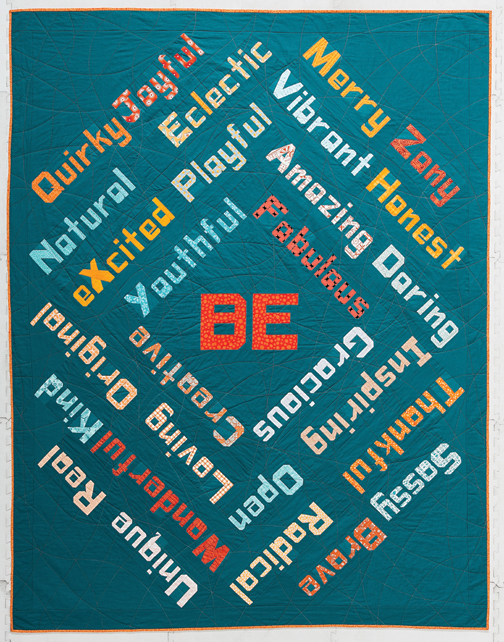

BE Amazing (from Quilt Talk). Photo credit: C&T Publishing.

Do you consider yourself a “quilter”, an artist, or some combination of both?

Sam: Yes, to all of the above. It took me a while in my life to claim the title of “artist.” I have never been great at drawing and took my failure at it to mean that I could never be an artist — especially when you add that to the unkind things people say to kids when they first start drawing (“elephants aren’t that color”). So many kids reject their artistic ability or curiosity because they took a careless comment to heart. We need to be way more careful about that, with kids and grownups alike. I once had a quilting teacher sneer “Oh, you’re a Crayola quilter” because I brought bright fabrics to class in the age of calicoes. It made me angry, once I got past wanting to shrivel up in embarrassment during the class. I’ve since been trained in how to draw, and I can do it passably. While I’m still not great at it, nor do I like doing it much… it’s always a struggle for me. I’m walking proof you can earn an MFA with middling drawing skills because art is about so much more than that.

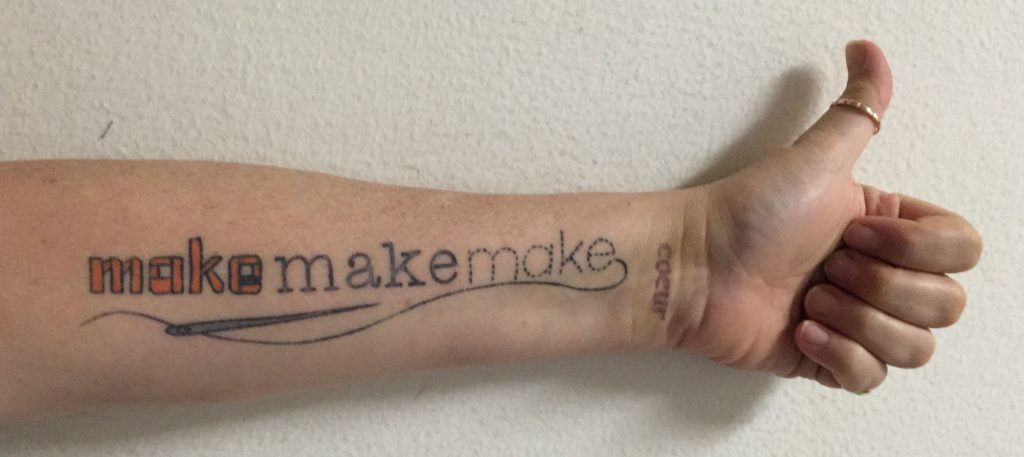

Sam’s tattoo, and ode to her life as a Maker. Image courtesy of Sam Hunter.

How would you define “making with intention”?

Sam: Exactly that. Having some type of intention sparking your making, whether that intention is to play, to make a competition quilt, to make a snuggle quilt, or to explore a new technique. Sometimes I make mundane things (like simple strip quilts) when I need to ponder something, because the rhythm of making soothes my body, so that my mind can sink in to the problem.

Do you think that having a craft makes us more compassionate? If so, then how?

Sam: I think being a maker gives us greater compassion for the handmade, because we understand the cost of labor and soul to produce something. I’ve given quilts to people who don’t quilt, who were like, “cool… another blanket”. The quilts I’ve given to quilting friends have a significantly bigger impact, because they know what they’re holding. Personally, I think it has given me a greater compassion for other artists and the gauntlets we all run to make our livings.

Sam’s work studio. Image courtesy of Sam Hunter.

How does creating feed your soul/spiritual purpose?

Sam: To my core, I’m a maker. I need to make art like I need air. It’s no more simple, nor complicated, than that. When I don’t make art I get weird, and that bodes poorly for the people around me :-)

Are there any rituals that you perform to prepare/ground yourself in your work?

Sam: I usually can get right to work. I feel like it’s a muscle that’s ready to go when it gets exercised enough, and I work at it all the time. I have a “centering sequence” of a few breaths/mantras that can settle me pretty quickly if I’m feeling scattered.

What is the support system you have in place for creating your work?

Sam: I’m one of the few that loves a tidy studio. I find it motivating and welcoming to come into clean space to work, with all my tools and fabrics organized. I spend the last 10 minutes of every day putting my tools away, logging my work, updating my lists, and prepping the first thing I will tackle in the morning. I find this helps me get to work, rather than dithering about what I’m supposed to be working on.

I also have a trusted set of pals to consult when I need an honest opinion. I follow some of the project planning methodologies created by Charlie Gilkey and Angela Wheeler of Productive Flourishing, and they say you need two teams of people in your work world. The first are the advisors, from whom you will take advice and critique. The second are the cheer team, who will celebrate your wins with you. Gilkey and Wheeler maintain that, especially for entrepreneurs who tend to work solo and are usually overworked, the celebration part of a completed project is really necessary. Also, I think you have to learn to listen to your guts… they’ll tell you what’s going on with you. And when they tell you to explore something, you need to pay attention to that. Curiosity is the spark of many a great creative journey.

Mortimer, pattern available here. Image courtesy of Sam Hunter.

How do you deal with comparison to/envy of others? Can you describe a time when you used comparison/envy/admiration to push yourself in your own work and self-discovery?

Sam: In this age of social media and extreme advertising, it’s impossible to avoid an onslaught of imagery that is designed to make you feel inadequate in just about every area of your life. Highlighting your shortcomings is a way to create the desire to make you want to buy a product. Even when I understand the mental game that’s afoot, it’s still really hard not to fall for wanting a thinner, glossier, better staged version of my life. But that’s really what it is – staging – and I try to keep that in view. Despite what you see on social media regarding quilt designers, what goes on behind the scenes is really human and messy.

I’m grateful that I have industry friends that I can share those shaggy bits with, who are as shaggy as I am. Few us have the types of studios that get featured in magazines…most of us are still overtaking any corner of the house we can appropriate to get our work done. So when I see the gloss, I try to remember my humanity. I count my accomplishments (7 years in business, 70 patterns and a book released, great relationships with most of the big fabric companies, etc.) and I try not to lose sight of the staging. I also have to remember that I’m solo and self-supporting in my biz. I don’t have a partner’s income behind me, nor their assistance. This means that I have to hire out a lot of stuff I know other designers’ partners take care of, or ask my pals to help. Both of those are wells I go to carefully.

Looking at the work of others is also something that I find needs to be done carefully. I want to see what my friends and peers are up to, and watch trends, but I also need to keep it all at arm’s length because it pollutes my design head. Up to a point, we’re all working with squares and rectangles and triangles in quilting, so there’re bound to be arrangements that feel like the work someone else is doing.

We also go through trends of stuff. A few years back I did a couple of patterns with prairie points in them. I thought it was a cool traditional element to play with, and a month later there was a prairie point quilt on the cover of a magazine. Sometimes the idea is just out there in the global creative soup, and more than one of us grabs it to run with it. Case in point, Libs Elliott and I both did skulls within a month of each other. But, if you look at them, you can see that the designs came from within us because they are so very different (mine is about the teeth, and hers, to me, is very much about the eyes). When I design, I make a point of not looking at anything else. I start with a blank slate and build it myself. I write and illustrate from scratch, unless I’m pulling an already written section from a previous pattern!

There are times I see something that just knocks my socks off, and I’ll thing “Dang! I wish I had made something that interesting!” I find that motivates me to dig deeper into what I’m trying to design. Personally, I’m interested in complicated things. However, as a designer, I hang out in the space of the beginner to intermediate quilter. Currently, the thing that interests me is block-of-the-month designs. I have one I’ve been playing with in the design queue, and there’s another that I’m batting around with some colleagues that we’re thinking of doing together next year.

Enlarged Heart. Image courtesy of Sam Hunter.

What was the most challenging thing you ever made?

Sam: In my fine art life, it was the first major piece I made after having a heart attack and finding out that I have genetic issues with my heart that can’t be solved. I was struggling with the shock and grief of it, but I was still in grad school, so I had to keep making art to fulfill my class requirements. The piece is huge and messy and wordless, and when I look at it now I can see the primal scream that I was trying to let out. It’s so different from the usual clean, almost architectural quality of my work.

In my quilt design life, my book, Quilt Talk, was probably the big one. It was a gargantuan project. It took the better part of a year to write and to sew, another half a year of wrangling it through the editing process, and then all the marketing you’re expected to do. I’m really proud of it, but it was a harrowing experience and I still feel like I couldn’t face doing another.

A challenge can be reaching beyond your current skills or chugging through something that is boring or working with a color palette that’s new or even a tight deadline. Challenges come in so many forms. Every project has a moment that challenges you. If you are committed to the project, what matters is that you shake hands with the challenge, and meet it. If you’re not committed to it, what matters is that you make an conscious decision to be with it, or to let it go. Not all challenges need to be met. But, they do require that you make a choice about it.

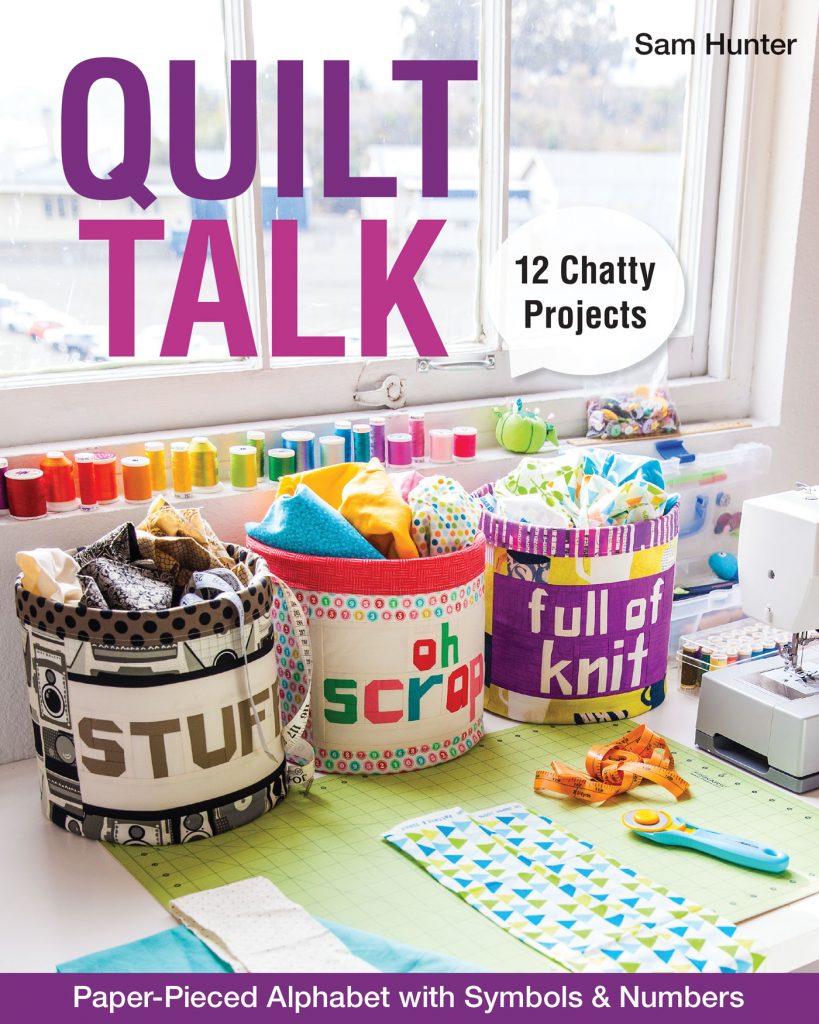

The cover of Quilt Talk: Paper-Pieced Alphabet with Numbers & Symbols – 12 Chatty Projects. Available on Sam’s website and other places books are sold! Photo credit: C&T Publishing.

What does it mean to you to work in a traditionally domestic medium that historically has been regarded as predominantly female (aka “women’s work)?

Sam: I consider myself to be part of a rich lineage, and I’m proud to carry it forward and be a teacher for our next generations. The women’s work thing is a huge issue. Historically, it has been disrespected and undervalued and that is still the case today. Women have not been taught to claim their worth, so it can be super hard to put a price on your time or work. But we must.

We must educate our buyers as to why what we do has value. Whether we need the money or not, we must still charge an industry-appropriate price, because, in the end, it supports us all. I’ve seen instances where a long-arm artist will undercut the other long-armers in an area and it’s awful. We shouldn’t be in a race to get to the soup kitchen. We should be in a race to build a stable, profit-earning industry that supports everyone with a livable wage.

I hate this idea that if you work in the arts you should be happy with peanuts because you LOVE what you do. I see a lot of bankers driving very nice cars who love what they do. It should be no different for the arts, or for women in artistic fields. Earning money is not a sordid thing, and we need to get past that. If we support each other in reasonable pricing, we will all rise together.

I don’t feel that I can address what it means to be a woman in quilting without touching on topic of men in the industry. I feel there is plenty of space here for anyone who wants to join, but, I’m a bit tired of middlingly talented fellas being elevated merely because they are guys.

Men in quilting are by nature oddities, so they stand out, which makes it easy to choose them for shows or magazine articles. I find it a bit lazy, actually. Every time I see one of those, I think about the twenty women I could easily name whose work is far more deserving of the accolades and opportunities. I think it’s time for us to celebrate the talent and to stop following the shiny.

How do you see your current work in the context of quilting history?

Sam: I know that my book will allow historians to date projects that use its alphabet, which is a really cool thing. I hope that my patterns help people have more fun making more stuff. I don’t want to design something that would make a quilter quit! I want my customers to get all the joy from quilting that I get, no matter what their skill level. I also want them to experience the wonderful community that surrounds quilting – I’ve met most of my closest friends over the years through quilting. I also want to treat my customers well for the sake of my industry. If we chase people out of quilting with poorly designed patterns or terrible customer service, then my entire industry is at risk. I feel a responsibility for both my customers and my colleagues to do the best I can. The legacy I hope to leave behind for my customers is that my patterns were makable and approachable. The legacy I hope to leave behind in the industry is that, because I fought for us, we all get paid a living wage.

Thank you, Sam! Your voice as an advocate for women working in the industry is an inspiration and I hope you continue educating and empowering artists through your We Are $ew Worth It campaign! For more about Sam visit her website, Hunter’s Design Studio. Also, connect with her on Instagram, Facebook or Pinterest.

Want to participate in the Creativity Project? You can do that! Click here to take the survey!

The Creativity Project can be found on Instagram, Pinterest, Twitter or Bloglovin’. Or check back here every Friday of 2018!

5 Comments

Comments are closed.

Fantastic interview; thanks again for curating these!

Thanks Yvonne! This was a fun year meeting so many quilters, artists, and makers and learning about their process. So glad you enjoyed!

Fantastic interview! Many things you said resonated, especially this, as I’m a longarm quilter with recent locals undercutting with cheap prices: “I’ve seen instances where a long-arm artist will undercut the other long-armers in an area and it’s awful. We shouldn’t be in a race to get to the soup kitchen. We should be in a race to build a stable, profit-earning industry that supports everyone with a livable wage.”

We shouldn’t be in a race to the soup kitchen! So true.

Terrific interview and thoughtful questions.

So So True Corni! So glad that hit home for you too! Sam has been an important advocate for this.

Great Interview – I’ve made a few patters from HDS, and they are all so well written. Thanks Sam!